Central vs. Peripheral Vision: What Athletes Need to Know

ou have two ways of seeing. Most athletes only train one.

Look at a word on this page. Notice how the letters around it get blurry? That's the difference between central and peripheral vision.

The Sharp Center

Your central vision comes from a tiny spot called the fovea. It sits at the back of your eye. This spot is packed with cells that see fine detail. But it covers only about 2 degrees of your visual field. That's roughly the size of your thumbnail held at arm's length.

Everything outside that tiny circle is peripheral vision. It stretches about 200 degrees around you. But the detail drops fast. By 40 degrees from center, you've lost about 90% of your sharpness.

So what can your peripheral vision do? It detects motion really well. The cells in your outer retina evolved to notice movement - threats coming from the side. You see something move out of the corner of your eye before you know what it is.

What This Means for Sports

Here's where it gets interesting. Research shows that expert athletes use both systems in smart ways.

For aiming tasks - shooting a free throw, putting a golf ball, hitting a target - experts use a gaze pattern called the Quiet Eye. They lock their central vision on one spot and hold it steady before and during their movement. Dr. Joan Vickers at the University of Calgary discovered this pattern in 1996. Her research shows that longer, steadier fixations lead to better accuracy.

But in team sports and defense, experts do something different. Research shows that skilled basketball defenders often look at empty space between players. They don't track any one person. Instead, they park their gaze in the middle and use peripheral vision to watch everyone at once.

Researchers call this "gaze anchoring." The athlete's sharp focus stays in one spot. Their peripheral vision does the rest.

Why Both Systems Matter

Think about what each type of vision does best:

Central vision sees detail. You need it to aim at a small target. You need it to read spin on a ball. You need it when precision matters.

Peripheral vision detects motion. You need it to notice a defender cutting behind you. You need it to track multiple players. You need it when awareness matters.

A martial arts study showed this clearly. Fighters in Qwan Ki Do (who face attacks from hands and feet) anchor their gaze higher on the opponent's body than Tae Kwon Do fighters (who mainly face leg attacks). They adjust their gaze anchor to cover the areas they need to monitor.

Training Both Systems

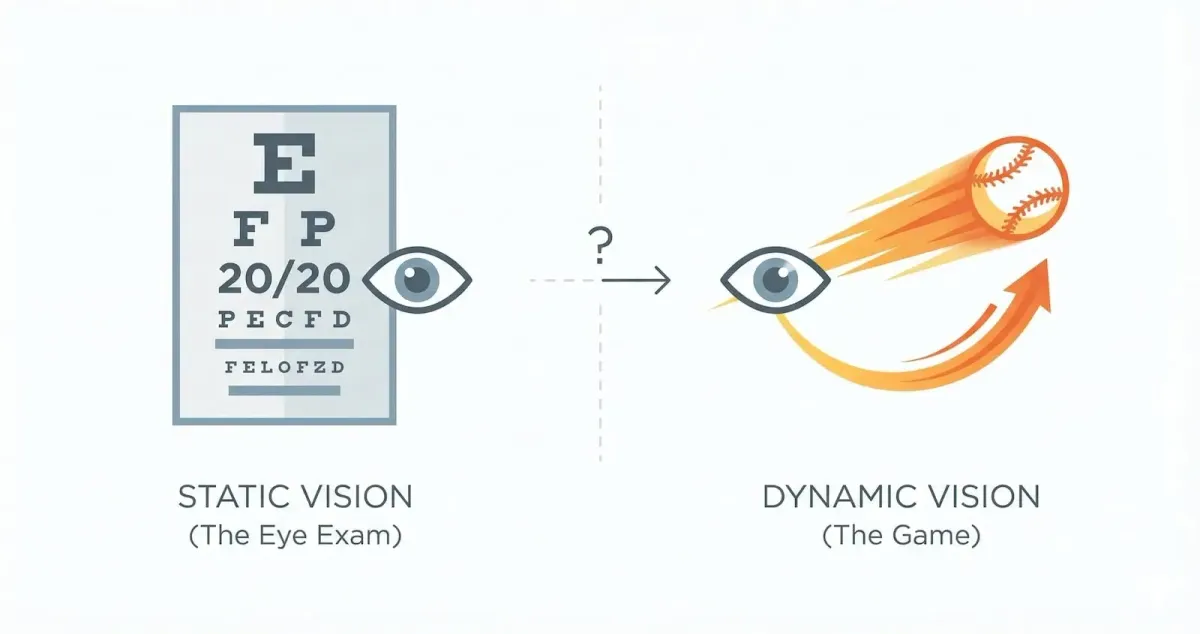

Most vision training focuses on central vision—tracking a single point, reading smaller letters. That helps for precision tasks.

But peripheral awareness training is different. It teaches you to process more information from the edges of your vision. Athletes who develop this skill often say they can "see everything at once."

Both skills improve with practice. What matters is matching your training to your sport:

Aiming sports (golf, archery, shooting, free throws): Central vision dominates. Practice holding steady focus on your target.

Team sports (basketball, soccer, hockey): Both matter. You need sharp focus to shoot but wide awareness to play defense and find teammates.

Interceptive sports (baseball, tennis, goalkeeping): You shift between them. Peripheral vision detects the ball; central vision tracks it.

The Bottom Line

Your eyes don't work like a camera that sees everything equally. The center is sharp. The edges detect motion but miss detail.

Elite athletes adapt their gaze to the moment. Sometimes they lock focus tight. Other times they anchor their gaze in space and let peripheral vision do the work.

Understanding this is the first step. Training both systems is the next.

Research References

- Klostermann A, Vater C, Kredel R, Hossner E-J (2020). Perception and Action in Sports: On the Functionality of Foveal and Peripheral Vision. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living. Full Text

- Hausegger T, Vater C, Hossner E-J (2019). Peripheral Vision in Martial Arts Experts: The Cost-Dependent Anchoring of Gaze. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. PubMed

- Vickers JN (1996). Visual control when aiming at a far target. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. PubMed

These exercises challenge and develop eye movement skills. They are not medical treatment. If you have concerns about your vision, see a qualified eye care professional.