Why 20/20 Vision Doesn't Mean You Can Hit a Fastball

Your optometrist says your vision is perfect. You can read the bottom line of the eye chart. 20/20.

So why does the ball seem to disappear halfway to the plate? Why can't you pick up that crossing clay target? Why do you struggle tracking a pass in dim gym lighting?

Here's the uncomfortable truth: the standard eye exam tests the wrong skill for most sports. And better testing exists-you just have to know to ask for it.

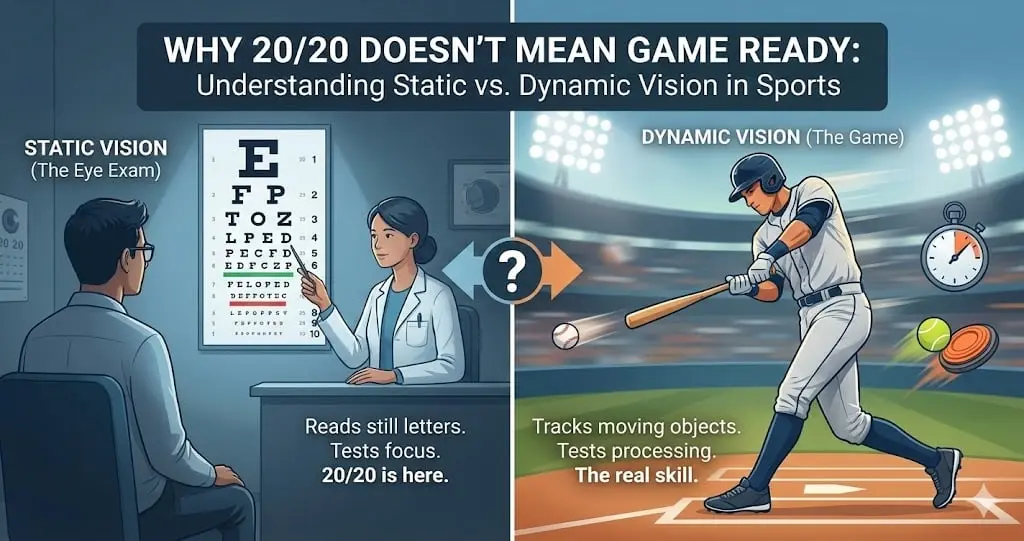

What 20/20 Actually Measures

The Snellen chart—those progressively smaller letters on the wall—has been the gold standard since 1862. It measures one thing: how sharply you resolve high-contrast stationary details at 20 feet.

20/20 means you can identify letters at 20 feet that a person with "normal" vision can identify at 20 feet. That's useful. It tells your doctor whether your eyes are focusing light correctly onto your retina and whether you need corrective lenses for driving or reading.

But consider what the test requires: you sit still, the chart sits still, the lighting is optimal, you have unlimited time, and the letters are black on white-about as high-contrast as it gets.

Now consider what a fastball requires: a 3-inch sphere traveling 90+ mph, spinning 2000+ RPM, potentially breaking in multiple directions, viewed against variable backgrounds, with roughly 400 milliseconds to see it, process it, and swing.

These are fundamentally different visual tasks. And the standard eye exam only tests one of them.

Static vs. Dynamic Visual Acuity

Vision scientists distinguish between static and dynamic visual acuity. Static acuity is your Snellen score - how well you resolve stationary detail. Dynamic visual acuity (DVA) measures how well you resolve detail when either you or the target is moving.

The critical finding: these skills don't correlate as strongly as you'd expect. A 2021 study from the University of Waterloo tested athletes, video game players, and non-athletes, all with similar static visual acuity around 20/20. When targets moved at 30 degrees per second - roughly the angular velocity of a crossing tennis ball - significantly outperformed both other groups.

Here's what's interesting: the researchers also measured smooth pursuit eye tracking, and all groups performed similarly. The athletes weren't moving their eyes better. They were processing the moving visual information more efficiently. Something about athletic training had enhanced their ability to extract detail from motion.

Similar patterns show up across studies. Professional soccer players with excellent dynamic acuity don't necessarily have better static acuity than amateurs. The skills appear to be at least partially independent -which means training one doesn't automatically improve the other.

What Else the Standard Exam Misses

Beyond dynamic acuity, several visual skills matter for sports performance that don't appear in routine eye exams:

Contrast sensitivity measures your ability to distinguish objects from backgrounds when the difference isn't stark—a white ball against clouds, a brown football against a muddy field, an opponent in similar-colored gear. The Pelli-Robson and Mars charts test this using gray letters at varying contrast levels against white backgrounds. You can have 20/20 acuity and still struggle in low-contrast conditions.

Depth perception (stereopsis) relies on your brain integrating slightly different images from each eye to calculate distance. The standard exam checks if you have it, but not how precisely. Fine-grained depth perception affects everything from judging a fly ball to calculating lead on a moving target to threading a pass through traffic.

Vergence and accommodation describe how well your eyes coordinate when tracking objects at changing distances. Vergence is the ability to point both eyes at the same spot; accommodation is the ability to refocus as distance changes. Problems here create fatigue, blur, and tracking difficulties that don't show up on the Snellen chart.

Eye tracking ability encompasses both smooth pursuit (following moving objects) and saccades (jumping between fixation points). Poor tracking can mean losing the ball mid-flight or struggling to scan a field efficiently.

Visual reaction time measures how quickly your visual system detects and responds to stimuli. This involves both sensory processing and motor response initiation.

None of these appear in a routine eye exam, even though all of them affect athletic performance.

What to Ask For: The Sports Vision Exam

Sports vision testing goes by several names—sports vision assessment, performance vision evaluation, binocular vision assessment—but the core idea is the same: a battery of tests that evaluate visual skills beyond static acuity.

If you're looking for this kind of testing, here's what to know:

Where to find it. Not every optometrist offers sports vision services. Look for practitioners who specifically advertise sports vision or performance vision testing. The International Sports Vision Association (ISVA) maintains a directory at sportsvision.pro. The College of Optometrists in Vision Development (COVD) at covd.org is another resource, particularly for binocular vision specialists. You can also ask your regular optometrist for a referral.

What to expect. A comprehensive sports vision assessment typically takes 60-90 minutes and may include:

- Standard visual acuity and refraction (to establish baseline and prescription needs)

- Contrast sensitivity testing (often Pelli-Robson or Mars charts)

- Stereopsis/depth perception (Randot, Frisby, or similar tests)

- Ocular motility testing (tracking ability, saccades, pursuit)

- Vergence testing (convergence/divergence amplitude and facility)

- Accommodative testing (focusing flexibility and amplitude)

- Eye dominance assessment

- Visual reaction time testing

- Peripheral awareness evaluation

Some clinics use computerized systems like RightEye or Senaptec that provide standardized sports-specific measurements and can track progress over time.

What it costs. Sports vision testing is typically not covered by standard vision insurance, since it's considered performance enhancement rather than medical necessity. Expect to pay out-of-pocket, often $150-400 depending on the comprehensiveness of the evaluation.

What you'll learn. The assessment identifies specific visual weaknesses that may be affecting your performance. Maybe your depth perception is fine but your accommodative flexibility is slow. Maybe you track smoothly but your peripheral awareness is underdeveloped. This specificity matters because it directs training to actual deficits rather than generic exercises.

The Age Factor

Dynamic visual acuity appears to peak earlier and decline faster than static acuity. One study found DVA involving smooth pursuit peaked around ages 19-24, with measurable decline thereafter. Static acuity often remains stable much longer with proper correction.

There's good news for older athletes, though. Research on martial artists found that older practitioners who continued training maintained better dynamic visual acuity than age-matched non-athletes. The visual demands of their sport appeared to slow the typical age-related decline.

This suggests "use it or lose it" applies to dynamic visual skills just as it does to physical conditioning. You may not be able to prevent age-related decline entirely, but you can likely slow it by continuing to challenge your visual system.

Can You Actually Improve These Skills?

This is where the evidence gets complicated. Some visual skills clearly respond to training. Vergence and accommodation problems, for instance, often improve significantly with targeted exercises—this is the basis of vision therapy for conditions like convergence insufficiency.

The evidence for training already-normal visual skills to above-normal levels is more mixed. A 2011 review in the journal Eye & Contact Lens concluded that while athletes often demonstrate superior dynamic visual acuity compared to non-athletes, "the development of a standardized dynamic visual acuity test is needed as are well-controlled scientific studies to evaluate the benefits of sports vision training."

That said, athletes at the highest levels take this seriously. MLB teams conduct extensive visual testing. The U.S. Olympic Training Center has sports vision specialists. Professional shooters train their gaze patterns. These programs wouldn't persist if teams saw no benefit.

The most reasonable conclusion is probably this: vision training likely helps identify and correct deficits, may enhance specific skills when training is well-designed and targeted, but isn't a magic bullet that will transform mediocre vision into superhuman perception.

The Bottom Line

If you've struggled with fast-moving targets despite "perfect" vision, you're not imagining things. Static visual acuity - what the standard eye exam measures - is just one component of visual performance. Dynamic acuity, contrast sensitivity, depth perception, eye coordination, and tracking ability all matter for sports, and none of them appear on the Snellen chart.

Sports vision testing exists, and it's increasingly accessible. Whether you pursue formal assessment or simply become more aware of the visual demands your sport places on you, understanding what you're actually asking your eyes to do is the first step toward addressing the gap between 20/20 and seeing what you need to see.

Your optometrist can tell you if your eyes focus light correctly. That's valuable. But it's not the whole story.

Research References

- Yee A, Thompson B, Irving E, Dalton K (2021). Athletes Demonstrate Superior Dynamic Visual Acuity. Optometry and Vision Science. PubMed

- Erickson GB (2011). Visual Acuity and Contrast Sensitivity Testing for Sports Vision. Eye & Contact Lens. PubMed

- Jorge J, Fernandes P (2019). Static and dynamic visual acuity and refractive errors in elite football players. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. PubMed

- Muiños M, Ballesteros S (2015). Sports can protect dynamic visual acuity from aging. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. PubMed

- International Sports Vision Association. Sports Vision Testing. sportsvision.pro

Visual training exercises are designed to challenge and develop eye movement skills. They are not medical treatment. If you have concerns about your vision or eye health, see a qualified eye care professional.